Literature takes a great deal of living with and living by. George Steiner, Language and Silence

I'm glad you read the Candide of Voltaire. I think of the book more as an allegory (like the one of the Cave by Plato) than as a novel, because it can be read in so many different ways. And, between my current reading and your interpretation, not only are there many points in common, but also a great difference, which is exactly what I enjoy when we read the same books together.

In general, I think that in the beginning of reading is a concern, something that deeply troubles us personally and for which we look for healing and voice. This explains why each of us find different books to be consoling (= healing) -- or, just as in our own case, find different aspects of the same book to be particularly interesting.

For me, the aspects of Voltaire's book that I find interesting (at least as of now) are not so much about whether or not the world is the best of all possible worlds, but about the vision of life, the morality that Candide puts forward.

☆ ☆ ☆

When I read the book for the first time (in August 2022), I had two deeply serious, adolescent concerns about who I was. The first is that there were very few places where I could feel at home (which is serious enough). The second is that I was not allowed to see Ms ... more often (and this is very serious). And these were the sources of insecurity that had been in my mind since 2017.

Candide, like me, had these problems. He was expelled from the castle (his home), and he also became unable to see Miss Cunégonde for a long time.

He then travels a lot and meets many new people. He witnessed and experienced many shocking events (how many times did he cry out « hélas ! » in the story?). But amidst all this, he never lost his hope of seeing Cunégonde again, and it was precisely this that kept him alive, and, I argue, that truly made him mature.

☆ ☆ ☆

Towards the end, he meets a wise farmer in Turkey who tells him to stop thinking too philosophically and instead focus on what he can do, without listening to the noises of things happening in some faraway cities. He thus settles in a garden and starts working, using his hands to cultivate the garden. Candide, having seen many tragedies of the world, learns that in such turbulent and difficult times, the surest place for us to find peace, quiet, and order is the garden that we keep every day.

Here, I take the garden to be metaphorical (and not literal), because it's not as if Voltaire is telling everyone to become an actual farmer (it was long before communism). For me, the garden is a symbol of things that we do every day, of habits that we keep at constantly, of skills that we develop inside ourselves. The garden therefore is inside, in my heart.

Furthermore, the garden became home for Candide. It gave him nourishment, and a sense of belonging, security and peace. There, working with and surrounded by his friends, he belonged to a warm, welcoming community.

Thus, the place where I should look for home is not to be found outside -- in this town, with this person, before this landscape, with this object and so on --, but inside: it is in the garden kept inside me that I feel most at home. So, when I set out to travel from now on, I will feel at home anywhere.

☆ ☆ ☆

Also, it didn't matter that Cunégonde looked rather unpleasant now: she had given him a strong hope to live on, and the very long journey that made him grow. She has nothing more to offer him. Someone who kept on waiting and did not rush, who never lost one's hope nor vision, should not feel deceived by the 'Cunégonde' who turned out to be poor, but be grateful for the marvellous journey that she gave.

As Seneca writes in his Moral Letters to Lucilius (No. XXVIII) --

Magis quis veneris quam quo interest.

The person that you are is more important than the place to which you go.

君がどこへたどり着くかよりも、そのときに君がどんな人間であるかのほうが大事だ。

☆ ☆ ☆

And this, I think, connects directly to what you said about the relation of regret (a negative feeling) to the imperfect world.

Our circumstance may not be the best: but we should at least do everything that we can, try to do our best. We are not guaranteeing success, but we must guarantee effort.

We should therefore keep on trying, however many times we should fail, however imperfect the world may be. There are more reasons to be optimistic in a suboptimal world. And Voltaire himself, I am sure, would have approved of your upstanding attitude.

This philosophical aspect of the novel (which is its main theme) used to be less familiar to me before I heard about your interpretation. But now I see it much more clearly. So, thank you for helping me read the book in new ways!

☆ ☆ ☆

母方の祖母が5歳になる終戦の年、満州から (徒歩で!) 引き揚げて来る際、家族は布を巻いて履く

この経験から、曾祖母は子ども達に身についたものだけが失われない富、だからお金は貴金属よりも本のために使い、そこから血肉にした知識と学びと経験とだけを、自分から奪われない真の豊かさとするように、と教えた・・

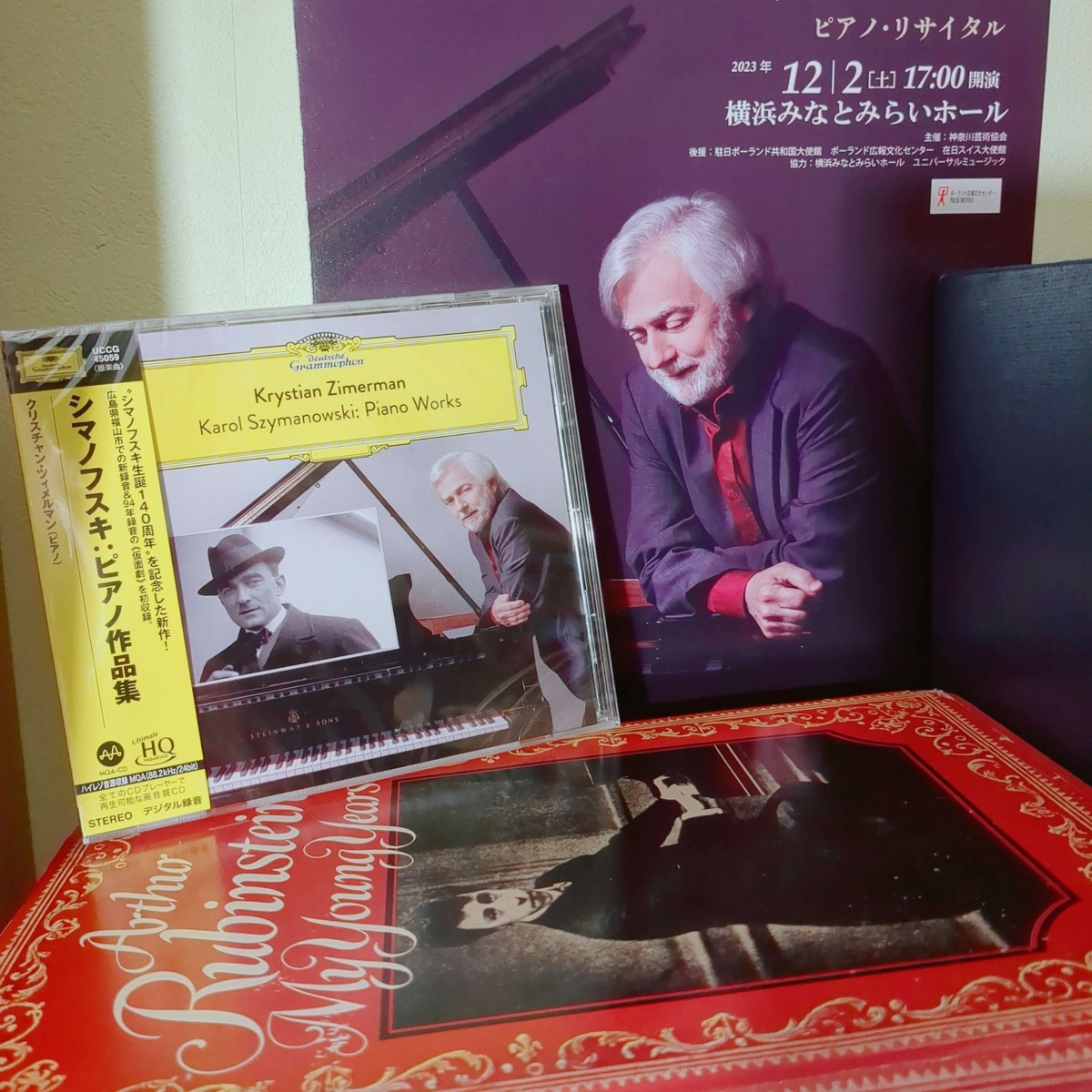

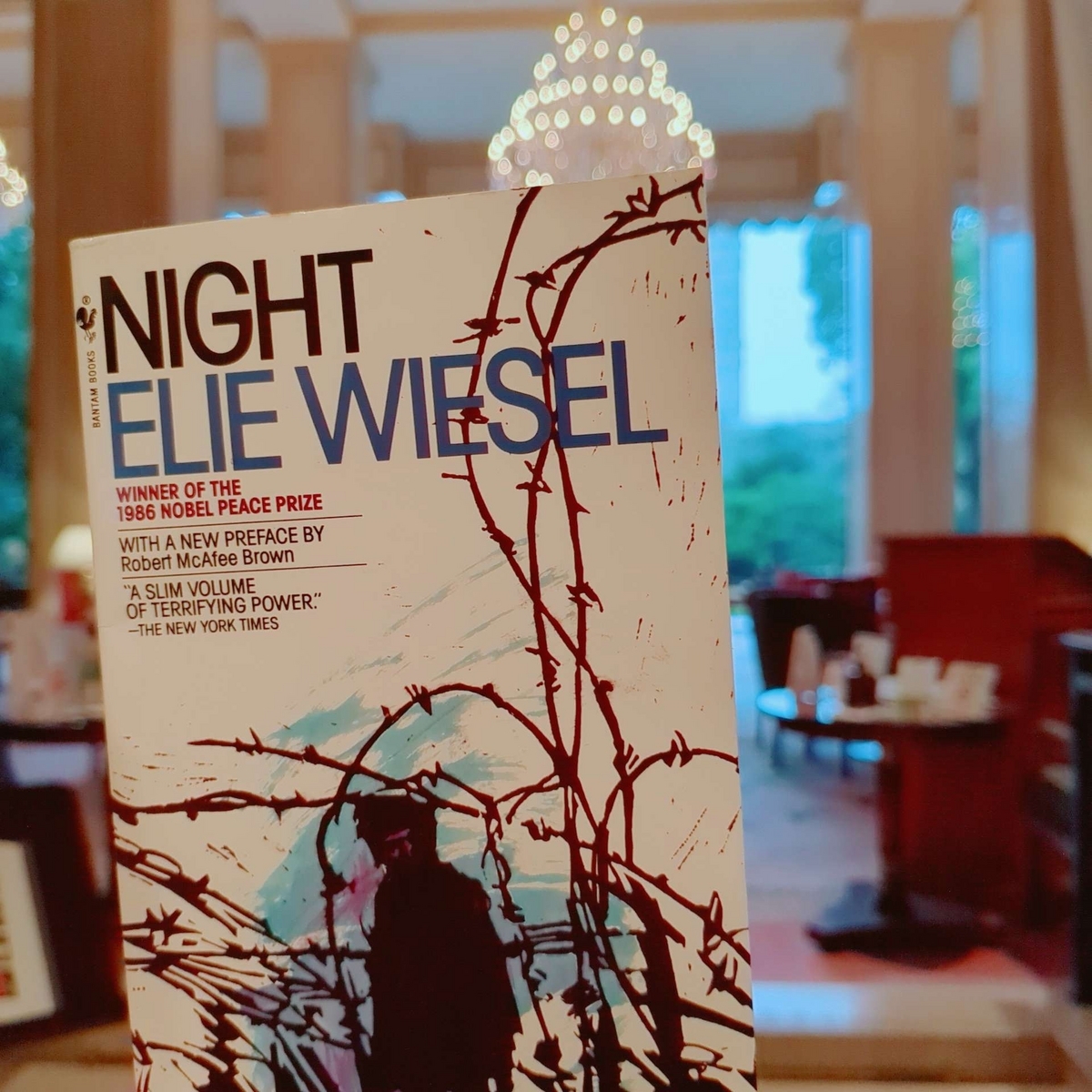

もちろん本だけに限らず、それは Rubinstein や Argerich のようにピアノが弾けることかもしれないし、Proust や Wiesel のように記憶と文学かもしれないし、Weil や Hofstadter のように多言語と数学かもしれないし、Chomsky や George Steiner のように哲学と言葉かもしれない。

それが何であるにせよ、自分の身につけられたもの、何よりも学びと記憶こそが自身の家系譜に受け継がれてきた伝統と遺産であるのだと、14歳のときに初めて訪れた神保町の友愛書房でヘブライ語文法と英ヘ対訳聖書を手に入れた自分は、ユダヤ文学と先祖に教えられたのであった。

☆ ☆ ☆

For us, home is memory. ... Learning is also a home.

Learning is what keeps us attached to our ancestral home.

Elie Wiesel: Longing for Home, Today (92NY)

Vivent les lettres ! vivent les arts ! vivent ceux qui ont un peu de goût pour eux, et même un peu de passion ! Monseigneur, plus je vieillis, plus je crois, Dieu me le pardonne, que je deviens sage : car je ne connais plus que littérature et agriculture. [...] J’ai été bien attrapé quand j’ai vu que la terre est couverte de gens qui ne méritent pas qu’on leur parle.

Voltaire, À M. Le Cardinal de Bernis, 26 juin 1762

« Il était tout naturel d’imaginer qu’après tant de désastres, Candide marié avec sa maîtresse, et vivant avec le philosophe Pangloss, [...] ayant d’ailleurs rapporté tant de diamants de la patrie des anciens Incas, mènerait la vie du monde la plus agréable ; mais il fut tant friponné par les Juifs, qu’il ne lui resta plus rien que sa petite métairie ; sa femme devenant tous les jours plus laide devint acariâtre et insupportable » (ch. XXX)

iustitia, virtus, prudentia, hoc ipsum, nihil bonum putare quod eripi possit

the qualities of a just, a good and an enlightened character, and indeed the very fact of not regarding as valuable anything that is capable of being taken away

Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucilius, No. XI (tr. Robin Campbell)

豊かさとは物資の豊富さよりも、むしろ裸一貫でも出発できるような、身についた技能や意欲が心にみちみちていることを言うのではなかろうか。このほうが失われにくい富ではないか。その技術も意欲も人にとっていろいろな方向をむいていることだろう。社会と文化の厚みをつくるうえでそれはぜひとも必要なことだ。ともかく身についたもの、心にあふれるものがあれば、きびしさの体験は個人にも社会にも新しい段階への飛躍のバネになることが決して少なくない。ヴォルテールの有名な短編 (1759) の主人公カンディードが言うように、世の中が思わしくない時には「われらの庭をたがやしていなくてはならない。」... 神谷美恵子『存在の重み』「初夢」pp. 208-9

my children’s eighty-six-year-old Jewish grandmother, Lotte Noam … On almost any occasion she can supply an appropriate three-stanza poem from Rilke, a passage from Goethe […] Once, in a burst of envy, I asked Lotte how she could ever memorize so many poems and jokes. She answered simply, “I always wanted to have something no one could take away if I was ever put into a concentration camp.” Lotte prompts us to pause and consider the place of memory in our lives, and what the incremental atrophying of this quality, generation by generation, ultimately means. Maryanne Wolf, Proust and the Squid, ch. 3

The arts of memory are correlative with those of all higher literacy. They constitute the bridge between the oral and the written. Plato fears writing precisely because it will enfeeble the muscles of memory; hence, the central, crucial, irreplaceable role of learning by heart. What you love, you start learning by heart. […] For what you love, you will want to have inside you. We learned Pope’s Iliad by rote. We learned Lear’s nonsense rhymes by heart. Those children learned to tell the two apart and never say, "that ought I wrote in love I wrote only for love of art." These lines of Robert Graves accompany me day and night. But there are so many others. What you have by heart, no one can touch. They cannot take it from you. George Steiner, on the History of Literacy https://youtu.be/EH0MXdeGwSE&t=716

« Candide, dans le fond de son cœur, n'avait aucune envie d'épouser Cunégonde. »

[...] Keep Ithaka always in your mind. Arriving there is what you’re destined for. But don’t hurry the journey at all. Better if it lasts for years, so you’re old by the time you reach the island, wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way, not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey. Without her you wouldn't have set out. She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you. Wise as you will have become, so full of experience, you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

C. P. Cavafy, Ithaka (tr. Edmund Keeley)

[H]e who gives himself to a lover because he is a good man, and in the hope that he will be improved by his company, shows himself to be virtuous, even though the object of his affection turn out to be a villain, and to have no virtue; and if he is deceived he has committed a noble error. For he has proved that for his part he will do anything for anybody with a view to virtue and improvement, than which there can be nothing nobler. Thus noble in every case is the acceptance of another for the sake of virtue. This is that love which is the love of the heavenly goddess, and is heavenly, and of great price to individuals and cities, making the lover and the beloved alike eager in the work of their own improvement.

Plato, Symposium, a speech by Pausanias of Athens (185b), tr. Benjamin Jowett

« Que faut-il donc faire ? dit Pangloss. Te taire, dit le derviche. »

Ὅτι οὐδὲν ἦττον τὰ αὐτὰ ποιήσουσι, κἂν σὺ διαρραγῇς.

Even if you burst with indignation, they will still carry on regardless.

[仮に]君が怒って破裂したところで、彼らは少しも遠慮せずに同じことをやりつづけるであろう。

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 8.4 (tr. Martin Hammond, 神谷美恵子)

[...] ライストリゴン人、片目のキュクロプス、 ポセイドンの怒り、ああいうものにビクつくな。 士気が高ければ出くわさない。 身も心も喜び勇んでいたら、な。 ライストリゴン人、キュクロプス、 野蛮なポセイドンは出てこない。 来るとしたらきみの心に棲んでる奴。 きみがおのれの行く手に奴らを置くのさ。…

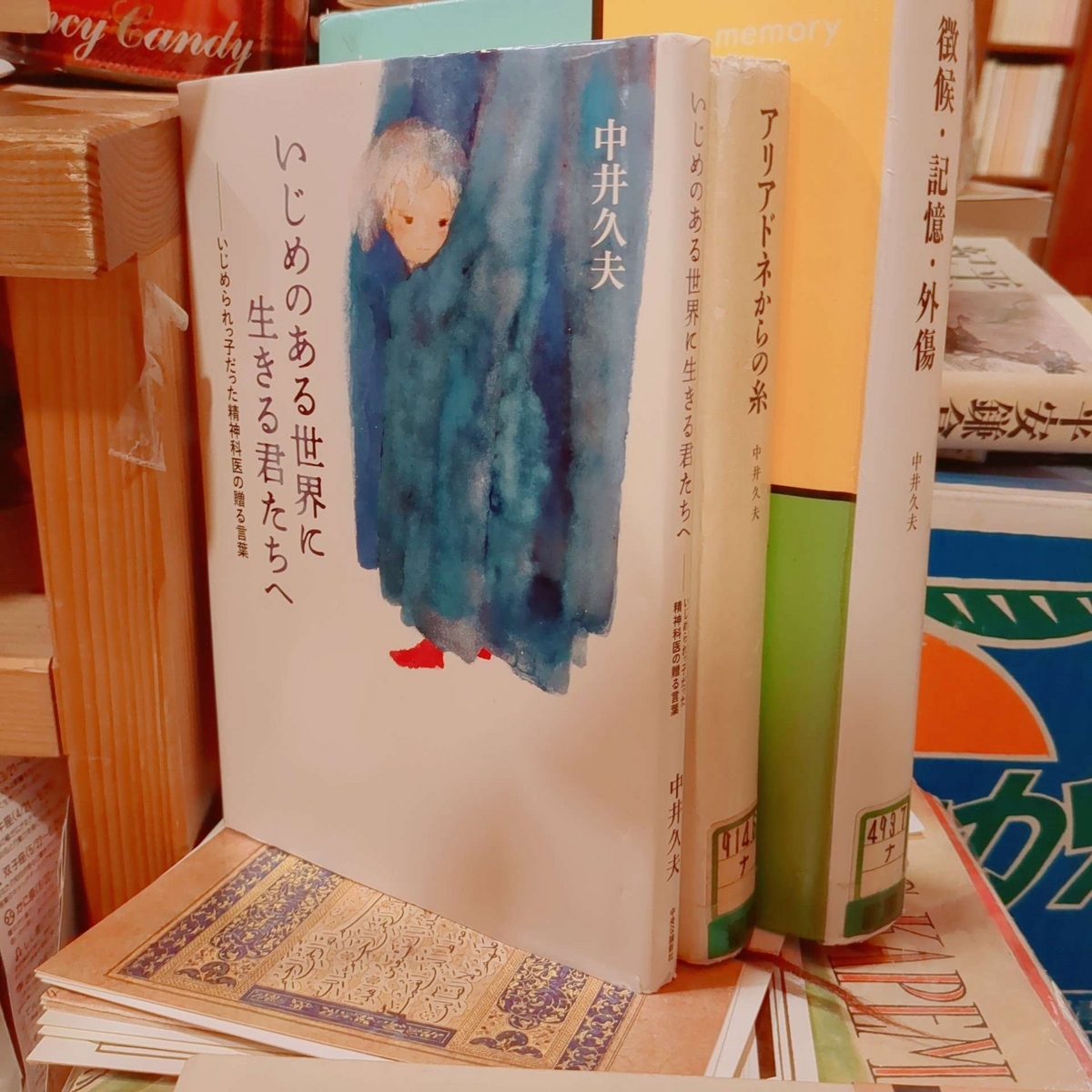

カヴァフィス「イタカ」(訳: 中井久夫)

On craignait plus l’oisiveté que les ennemis.

敵よりも自身の怠惰を惧れよ。

Montesquieu, Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (1734), ch. II

« je ne m’informe jamais de ce qu’on fait à Constantinople ; je me contente d’y envoyer vendre les fruits du jardin que je cultive ... avec mes enfants ; le travail éloigne de nous trois grands maux, l’ennui, le vice, et le besoin. »

We are wont to say that it was not in our power to choose the parents who fell to our lot, that they have been given to men by chance; yet we may be the sons of whomsoever we will. Households there are of noblest intellects; choose the one into which you wish to be adopted; you will inherit not merely their name, but even their property […]; the more persons you share it with, the greater it will become.

Seneca, On the Shortness of Life, ch. XV

If you share money, it disappears But if you share knowledge, it increases. — Charles "Chuck" Vest (as qtd. by Shigeru Miyagawa)

「知性の経済学では浪費するほうが太る」というフランスの詩人の警句 中井久夫『清陰星雨』「バカげた質問ない米国」p. 237

« Le pain que je vous propose Sert aux anges d'aliment Dieu lui-même le compose De la fleur de son froment. C'est ce pain si délectable Que ne mange pas à sa table Le monde que vous suivez. Je l'offre à qui veut me suivre. Approchez. Voulez-vous vivre ? Prenez, mangez, et vivez ! »

Racine, Cantique IV.

Le pain de farine est bon, mais il y a du pain doux comme du miel, si vous vouliez y goûter, dans un bon livre; il faut que la famille soit en réalité bien pauvre qui ne peut, une fois dans sa vie, payer pour des pains si multipliables la note de leur boulanger. Bread of flour is good; but there is bread, sweet as honey, if we would eat it, in a good book; and the family must be poor indeed, which, once in their lives, cannot, for, such multipliable barley-loaves, pay their baker’s bill. John Ruskin, Les Sésames et les Lys, tr. Marcel Proust (1906)

« quand l'homme fut mis dans le jardin d'Éden, il y fut mis ut operaretur eum, pour qu'il travaillât »

I think what Judaism says ... it is to keep moving, to know that almost everywhere on this earth is worth working in, knowing human beings and trying to contribute something --- and this is Judaism for me. Face to Face: George Steiner talks to Jeremy Isaacs (17:43)

Le laboureur a beau parler des saisons, discourir de la façon de cultiuer la terre, deduire quelles semences sont propres en chacun terroir : car tout cela n'est rien s'il ne met la main aux outils, s'il n'accouple ses bœufs, et ne les lie à la charrue. Aussi n'est-ce grande chose (bien que ce soit quelque cas) de fueilleter les liures, de gazouiller et caqueter en vne chaire de la Chirurgie, de ses perfections, et comme c'est le premier instrument du Medecin, le premier cogneu, et le plus ancien, et le plus anciennement vsité et practiqué : et si la main (suiuant la signification du vocable) ne besongne, et s'il n'est mis en vsage par bonne raison. [...]

C'est lascheté trop reprochable de s'arrester à l'inuention des premiers, en les imitant seulement, à la façon des paresseux, sans rien adiouster et accroistre à l'héritage qu'ils nous ont laissé, non pour le laisser deuenir en friche, mais pour le cultiuer et embellir : leur demeurant, comme à peres et autheurs, l'honneur de la premiere intention, mais à nous quelque petite proportion de gloire, pour l'enrichissement et illustration : restant à la verité plus de choses à chercher qu'il n'y en a de trouuées.

季節がどうのこうのといくら言ったところで、またこの土地には何という種子が合うかと述べたところで、... その農夫が自分で工作具を握り、牛を組み合わせて、すき車につながない限りはだめである。... それと同様に、いくら書物をめくって、講壇に立ち、外科学がどうのこうのと、ぺちゃくちゃおしゃべりをしてみたところで、... 自分の手が実際に働いておらねばだめである。先人の創意になずみ、怠け者のようにただこれを模倣し、我々に残された遺産をふやすこともこれに付け加えることもせずにいることは、はなはだ咎むべき懈怠である。先人たちが遺産を我々に残してくれたのは、それを荒蕪地としてほうっておかせるためではなく、これを耕作し、これを美しくしてもらおうがためである。... これまでに見いだされたことよりも、はるかに多くのものを、事実のなかから更に捜し出さねばならない。...

Ambroise Paré, Av Lectevr (Oeuvres Complètes, Tome I, Ed. Malgaigne, pp. 7-8)

渡辺一夫『フランス・ルネサンスの人々』「ある外科医の話」(白水社版 p. 313)

« Cela est bien dit, répondit Candide, mais il faut cultiver notre jardin. »

... 各人が育てているものはちがうだろうが、今年も黙々とこつこつ「庭」をたがやしたいものだ。そして許されるものならば時どき作物の出来具合を互いにそっと見せ合って心をあたためあい励まし合って行こう。未来を担う若い人たちにこのことを特に期待したい。 神谷美恵子『存在の重み』「初夢」pp. 208-9

自分が書いたものを皆さんが読んでくださることをなぜ望んでいるかっていいますと、やはり私の人生の習慣と皆さんの人生の習慣がクロスする瞬間というふうなものを夢見る、ということがあるからです。そういうところにどうも自分が生きて仕事をしていることの意味を夢想しているということがあるからだと思います。 大江健三郎『人生の習慣』「小説の知恵」p. 175

In Ezekiel in the Old Testament, God dictates to the prophet a text and then says: 'I want you to eat the scroll.' Careful: eat is eat in Hebrew, has nothing metaphoric. Put in your mouth, and you eat it --- like a spy eats his secret message, we're told in spy novels. And the surprised prophet does it, and, of course, the meaning is it becomes part of you. It becomes totally part of you. […] You ingest it, you eat it, it becomes fiber of your fiber, heart of your heart, cor cordis sursum, and it will stay with you. And suddenly, you realise that the house of your own inside has wonderful furniture. Most of us don't create very much. So, to be able to find in our house a company of the master spirits, the great spirits, ... means you come to a very full house, a very full house. Of Beauty and Consolation, Ep. 4: George Steiner (33:12)